Anniversary

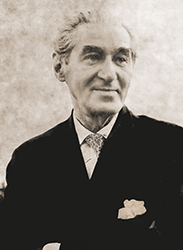

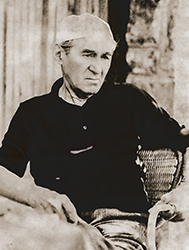

AN UNUSUAL INTERVIEW OF MILOŠ CRNJANSKI (1893–1977), EXACTLY HALF A CENTURY AGO

If Only My Eyes Can Last

Each poet has certain acts in their opus, like in a theater, a drama. If they develop, true poets are always interesting, even in their old age. Our people love poetry, literature in general; besides us, it’s only the case in Russia. Don’t believe writers who cannot write. Each writer enters something real into books, but it doesn’t mean that they write it as it was. When you grow old, critics usually stop attacking you, they don’t set you up or make jokes. You either find meaning in your life or you don’t, regardless of whether you are fertilizing earth or literature. I have been working on a book about him for eight years and was interested in Michelangelo for fifty years. A true poet cannot die before they fulfil their self, their fate

By: Jovan Pejčić

The interview the readers have before them was taken with Miloš Crnjanski on October 25, 1973, two days before his 80th birthday. I asked the great writer for an interview over the phone, at about 2:30 p.m., from the Student desk, Belgrade University students’ magazine (where I worked as editor for culture and literature at the time).

The interview the readers have before them was taken with Miloš Crnjanski on October 25, 1973, two days before his 80th birthday. I asked the great writer for an interview over the phone, at about 2:30 p.m., from the Student desk, Belgrade University students’ magazine (where I worked as editor for culture and literature at the time).

Miloš Crnjanski immediately accepted the interview. To have a students’ magazine interested in him – he said openly – ”is an honor to him”. He suggests, he continued, to have the conversation in his apartment, since his health is not too well. Since the Book Fair is currently in progress, and everyone is calling him, which exhausts him, he suggested we meet ”today if possible”, for example at four, and ”do the job” with the afternoon tea.

I admit that I began slightly panicking because of so many suggestions.

He asked me whether I would write down his answers or bring a tape recorder to note the conversation. I replied that I would do as he wished. Crnjanski said that, due to the little time he had, it’s better to talk ”into the tape recorder”.

However, the Student desk didn’t have a tape recorder. He couldn’t know it. I didn’t admit it to Crnjanski – I was, I still don’t know why, simply ashamed to do so. Rushing to get there at the agreed time (I had one and a half hour), I remembered Draginja Urošević, poetess, who worked on the radio at the time, in ”Beograd 202”. I asked her to, by any means, provide a tape recorder for my interview with Crnjanski.

So, Draginja and I arrived at Crnjanski’s home at 4 p.m. Maršala Tolbuhina Street 81, II floor, right from the stairway, apartment 8 – exactly above the ”Vltava” restaurant.

So, Draginja and I arrived at Crnjanski’s home at 4 p.m. Maršala Tolbuhina Street 81, II floor, right from the stairway, apartment 8 – exactly above the ”Vltava” restaurant.

My interview with Crnjanski lasted a bit less than three hours.

Student published my interview with Crnjanski on November 6, 1973 (no. 19, page 9), but not entirely and not in the form Crnjanski wanted it: the editor in chief planned ”one page for the conversation with Crnjanski – and that was it”. Thus, it happened that several parts of the authorized interview were omitted. And that – so to say – Crnjanski’s sentences-paragraphs were chained (with his approval) in a way entirely uncommon for him, into long wholes which in many places consequently seem as if the hand of Crnjanski had never worked on them. (...)

Now, exactly half a century later, on the 130th anniversary of Miloš Crnjanski’s birth, the interview is before the readers of National Review, in the form Miloš Crnjanski left it in the original version (which I consider the only genuine one). The interview on which Crnjanski and I, in October and beginning of November 1973, after taking out the tape, worked for almost two weeks.

Eighty years of living and, if we remember that you published your first poem in 1908, nearly seventy years of creative work, are irreputable proof of your deep life and creative experience. When you turn behind you today, what do you consider particularly important from all that, from your entire life?

Eighty years of living and, if we remember that you published your first poem in 1908, nearly seventy years of creative work, are irreputable proof of your deep life and creative experience. When you turn behind you today, what do you consider particularly important from all that, from your entire life?

The first and main impression is that chance wanted me to live eighty years and complete the road which I took in literature. The fact that I was writing in 1908 means that one poem was printed in Golub, a school magazine, and that many others, which I still keep, were not printed. I will leave them for people to see and laugh at my writing about Gundulić and how Gundulić is speaking on stage, because it’s interesting.

Second, as you say seventy and eighty years, it is a road which a poet takes in their development. If they are a true poet, of course, and if they don’t stop. It depends on their luck, literary, in life. If they grow, they’re always interesting, even in their old days.

All great poets abroad write until the age of seventy and eighty.

It happens that our poets, however, become silent very early. Those who experience a catastrophe, in their souls or life in general, become silent.

Yes, we do have poets who wrote until the end. For example, Zmaj Jovan Jovanović. He wrote his entire life. However, those who survived a tragedy in life, most of them, stopped. Perhaps because they couldn’t stand what was being written about them.

I survived all that and continued writing because I realized it was my vocation.

IT’S CLEVER TO STOP, BECOME SILENT

Wide is the arch of your poetry, from Lyrics of Ithaka to ”Lament over Belgrade”. On that long road, your most intimate aspirations, your most profound creative unrest, kept placing new challenges before poet Crnjanski, which, of course, requested new and different answers.

Wide is the arch of your poetry, from Lyrics of Ithaka to ”Lament over Belgrade”. On that long road, your most intimate aspirations, your most profound creative unrest, kept placing new challenges before poet Crnjanski, which, of course, requested new and different answers.

That is correct. Because every poet has, in their creative work, certain acts, as in the theater, in a drama. Lyrics of Ithaka was in my youth because it was such a time, revolutionary. They you have ”Serbia”, which is a bitter poem of love towards my nation.

Then I went abroad, to Italy. An entirely different life, when you are, so to say, forced to watch deeper into yourself. That is where ”Stražilovo” was created.

Then time passed.

Then came life abroad, twenty-five years. And then, at the end, in England, came the swan’s song, as I called it, ”Lament over Belgrade”.

Those are epochs of life, epochs of poetry. It’s normal for any poet. My first poetry and ”Lament over Belgrade”, they are, so to say, two different poetries.

There are, however, connections between them. You have, in Lyrics of Ithaka, poems which also sing about Belgrade.

Let me tell you, I came to Belgrade for the first time in 1908. My uncle lived here and ended in a madhouse, for political reasons. He was a Progressive, so the Radicals kept disturbing him, persecuting him. So, one day he entered the office, his office, sat on a cupboard, and started singing. He lost his mind. Nikola Vujić.

Let me tell you, I came to Belgrade for the first time in 1908. My uncle lived here and ended in a madhouse, for political reasons. He was a Progressive, so the Radicals kept disturbing him, persecuting him. So, one day he entered the office, his office, sat on a cupboard, and started singing. He lost his mind. Nikola Vujić.

I came to Belgrade often also because I had an aunt here, who lived in number 6, across the street from ”Moskva” hotel in Balkanska Street.

Belgrade was full of young people at the time. We used to gather there, where Dositej’s monument stands today. It was a joyful town, a merry place, which seduced me from the first day.

Those years I applied at the academy, fine arts, but didn’t pass.

So, I came as a football player.

Our generation was a generation of love for our nation, and for Belgrade.

Poetry started the same way too.

However, when you pass fifty, sixty years in life, your poetry is no longer madness. It is, always, a creative work, which suffers changes, constantly, and gains from them. You, therefore, then search for whatever more you want to say, you feel the end is near, and feel like you’re suffocating.

Just another remark, there is also so much reading from foreign poetries. You speak several languages, you get carried away by so many literatures, great tragedies, and great poets.

However, it’s clever to stop. Because, when one comes to my age, melancholy is so strong that it would be funny to continue writing poems. It would be miserable.

That is why I said that after ”Lament…” I will not write verses, and not publish. One should shut up.

FATE AND INFLUENCES

The poetry of your generation, especially your poetry, was first severely rejected by local literary critics. That lack of understanding for the new way of writing poetry, for a different, in many aspects negative attitude towards tradition, is – according to the general opinion – one of the essential reasons, if not the basic one, to write both the ”Explanation of Sumatra” and ”Comments of Ithaka”.

The poetry of your generation, especially your poetry, was first severely rejected by local literary critics. That lack of understanding for the new way of writing poetry, for a different, in many aspects negative attitude towards tradition, is – according to the general opinion – one of the essential reasons, if not the basic one, to write both the ”Explanation of Sumatra” and ”Comments of Ithaka”.

”Comments of Ithaka” are one thing, and ”Lyrics of Ithaka” something else. ”Comments” is life, which led to such poetry.

What you said about the critics, it was like that. It later, not only in my poems, happened. However, a writer, if they preserved their culture, entirely, can rule their critics. Critics, you know, don’t always have to be unpleasant.

It is funny, however, if there is an evil intention behind the critic, or something else, which has nothing to do with literature. There was much written about me, for example, and a lot invented.

However, that is behind me and, when I turn around, I see that was a path of fate, and that a true poet cannot die before fulfilling their SELF, their fate. I fulfilled my fate and I’m calm before future generations.

Could you please say which poets, writers in general, influenced you as an author. And I’m interested which poets you are reading now. Do you read our poetry, contemporary, the poetry of our youngest poets?

Could you please say which poets, writers in general, influenced you as an author. And I’m interested which poets you are reading now. Do you read our poetry, contemporary, the poetry of our youngest poets?

It is hard to answer. You know, while I was student of the gymnasium of catholic friars, in Timisoara, there was the influence, undoubtedly, of ancient writers.

When I left to Vienna University, the influence was undoubtedly of Germans, Goethe and others.

Then came the influences of the French, and Spanish, whom I love very much.

I have always enjoyed the poetry of foreign nations, of foreign poets. I read Camoes, Portuguese. Gongora, Spaniard, is a great poet for me. There are others as well: the entire Spanish poetry is pretty unknown in our land, although it is exquisite.

I return, constantly, to English poets, my own. I wrote about them for Literary Papers. They are Jeffrey Chaucer, Walter Raleigh, John Dan, Shelli…

Thus, many influenced me, and not only individuals, but entire literatures, and cultures. I will also mention the ancient Chinese, ancient Japanese lyrics.

They surely had an influence, if an influence is taken as something smart. However, if the meaning is that I imitated them, no. You will find a poem written by Dučić, which is an imitation. You can find Rakić’s poem, which is a translation from Shakespeare. We didn’t know it: about the beauty of that night in May…

They surely had an influence, if an influence is taken as something smart. However, if the meaning is that I imitated them, no. You will find a poem written by Dučić, which is an imitation. You can find Rakić’s poem, which is a translation from Shakespeare. We didn’t know it: about the beauty of that night in May…

No one will, however, find in my work, that any poet had such an influence on me. I didn’t stand it. It, you know, depends on your character as a writer.

You asked me if I read our poetry, I do, and with pleasure. The youngest ones as well. Only, that poetry is different. My poetry is the poetry of the heart, poetry of emotions, and theirs is the poetry of contemplation.

The thing, that we have hundreds of poets, it is a phenomenon of ours. Since, people here love poetry, literature in general. This is only the case in Russia. I haven’t seen it either in France or England. You, for instance, have great poets in England, among younger people as well, printed in a very small number of copies. Fifty-four million Englishmen, who have great poetry, in the past, and print two thousand copies for a man they considered a great poet.

SENTENCE GOES AFTER THE ESSENCE

Besides poetry, you started publishing prose very early. You have stories, novels, dramas. For a certain period of time, you wrote art criticism. You printed several essays about literature. Your travelogues belong to the supreme works of our travelogue literature. Did the so-called rules, implied by each of these styles, give you trouble?

Besides poetry, you started publishing prose very early. You have stories, novels, dramas. For a certain period of time, you wrote art criticism. You printed several essays about literature. Your travelogues belong to the supreme works of our travelogue literature. Did the so-called rules, implied by each of these styles, give you trouble?

A real artist is a born ballet dancer, and he dances different kinds of ballets. It is not true that great writers are only those who can write prose, and don’t write poetry. Or write only poetry, and don’t write prose, cannot write a drama, or something else. It is certainly wrong to think that those are true writers. An author can be great despite changing his tendencies.

It’s similar in music. Take Casals, for example. He chose the cello, but he also played the violin, extraordinarily, and made, if you wish, architectural music, which is for concerts.

That is how I created, in literature, what I wanted. I wrote poetry, I wrote novels, and drama, I believe that any writer, who does several kinds of literary works, is small, if they cannot be both a poet and prose writer. If there is poetry in prose, it doesn’t mean that they cannot write poems. Or, if there is prose in poems, it doesn’t mean that he has to be a poet.

You have to create with a wish to form your subconscious impulse.

Today, however, no one is speaking about the subconscious anymore. There was a short period in which people thought about it. However, the subconscious in poetry, prose, drama, in everything, has its role. Even when speaking about poetry in one era.

Take, for example, The Diary of Čarnojević. The poetry, which you find in this prose, it is the passion of the hero, he lives with it, it lives with him. He changes the way his life changes.

These are, you know, mutual relations. Without that poetry, he wouldn’t exist as such. It is his experience, his path into life. You remember, probably, the vibrations of his feelings in the cannonade, or in love with the Polish woman.

These are different things, certainly, which derive a different language, different sentence.

Your creative work gave an entirely new, unique stylistic technique, which was unknown in our, and not only our literature before your appearance. I mean, firstly, the structure of the sentence, your, to say the least, strange, wondrously expressive interpunction in both prose and poetic statements. The critics have recently seriously approached studying your literary expression, the uniqueness of the language you have introduced in literature. How do you explain your literary alphabet?

Your creative work gave an entirely new, unique stylistic technique, which was unknown in our, and not only our literature before your appearance. I mean, firstly, the structure of the sentence, your, to say the least, strange, wondrously expressive interpunction in both prose and poetic statements. The critics have recently seriously approached studying your literary expression, the uniqueness of the language you have introduced in literature. How do you explain your literary alphabet?

My language is, before all, clear and clean, and it attempts to present every thing in an appropriate way. A mother crying for her deceased son speaks differently than a peasant who is melancholic and sat down to get drunk. My sentence follows the essence of the situation it tells, the essence of the state of the soul it wants to tell the reader, and it does it.

As for the many commas, which many made jokes about – even Ivo Andrić made jokes once, about those commas – it is a wish to conquer the language, and to have the reader read the sentence the way I want them to read it, not as they would.

Vuk Karadžić, for example, didn’t need the commas, because he wrote folk things, folk language, so it went to the dot.

Today, however, in this time, when you tell hypermodern things, you have to make the sentence in the same way, to force the reader to see, and to read, the way you want them. Whether they’re satisfied or not, it’s another issue.

Accordingly, the artistic work in prose, and in poetry, means artistic values. You have to feel it, and to live with it. Don’t trust writers who cannot write. It is not a simple thing, being able to write what you want. Woe to those who are simple, they are boring writers.

AND WHEN YOU GET OLD...

Already at the time you published The Diary of Čarnojević, critics wrote that the book is autobiographic. The same, even more drastic, repeated with the book At the Hyperboreans. The Novel of London wasn’t spared in that sense either. You, in most cases, didn’t react to all those writings, so it was interpreted differently. What is your attitude to the issue of autobiographic in literature and, concretely, in your works?

Already at the time you published The Diary of Čarnojević, critics wrote that the book is autobiographic. The same, even more drastic, repeated with the book At the Hyperboreans. The Novel of London wasn’t spared in that sense either. You, in most cases, didn’t react to all those writings, so it was interpreted differently. What is your attitude to the issue of autobiographic in literature and, concretely, in your works?

All writers write biographically. There are no great or ordinary writers, who don’t write their life as well. If one of two brothers is a writer, and the other is not, it doesn’t mean that the writer will not write his brother’s experiences in the book.

What I experienced in World War I, it is in The Diary of Čarnojević.

However, the main character, it’s not only me.

It’s several people.

I will tell you what happened to me regarding that book. When I got married, you know, a famous millionaire from Belgrade rushed to my mother-in-law, and said: ”Listen, he is married. I saw the book where he wrote it!”

That’s how we people are like. And the woman, from the Diary…, it is a woman I barely knew.

Every writer enters something that is real in books. However, it does not mean that they enter it the way it really was.

Every writer enters something that is real in books. However, it does not mean that they enter it the way it really was.

At the Hyperboreans, I feel unpleasant because the book was so unnoticed.

I admit there, that it’s me writing. I was at Spitzbergen, I was on those journeys, I was in Rome, worked there.

But it doesn’t mean that my mistress came like that, and my wife like this, or that I was in love with this or that woman. It is not nice to ask a writer something like that. It’s ugly to be interested in it.

Much of it is biographical, because I experienced it. Since, for example, an event I’ve seen, the place where my wife’s sister drowned, on the same ship Dis was on, and my wife watching the sea and crying, it is, of course, autobiographic.

Or the man who is, in the Novel of London, prince Ryepnin. He existed. It’s just that he was Polish, not Russian, a Polish count. Many things, there in the book, are really from his life, not mine.

There are my friends, too, many of them. Some even recognized themselves. Some were even angry because of it.

In a relatively short period of time, three important books, we could say monographs, dedicated to your works, appeared. They are voluminous and on a high theoretical level, for which they were honored – studies of professor Nikola Milošević and Aleksandar Petrov. The third book is a collection of the Institute of Literature and Art in Belgrade, which, in works of various authors, encompasses almost everything you have published up to now. How did you accept these books?

In a relatively short period of time, three important books, we could say monographs, dedicated to your works, appeared. They are voluminous and on a high theoretical level, for which they were honored – studies of professor Nikola Milošević and Aleksandar Petrov. The third book is a collection of the Institute of Literature and Art in Belgrade, which, in works of various authors, encompasses almost everything you have published up to now. How did you accept these books?

When you grow old, critics usually stop attacking you, they don’t set you up, don’t make jokes.

Nikola Milošević, I wrote it to him from London, appeared as our first critic-scientist. His Novel of Miloš Crnjanski is everything that can be possible to interpret, favorably, to my benefit, in those novels.

Petrov has a mad diligence, which is fantastic. He, undoubtedly, found a connection between Russian futurism and me. And it’s no wonder he succeeded. However, as I said, he is so diligent that he not only studied each of my verses, but each third word I wrote, and I laughed so much because of it.

The collection is a thing I would like to say to the glory of women. There are, in that collection, very good essays.

There is, also, an attack on me, because that man doesn’t know that I knew much more about foreign politics than he thinks. And that I had a much greater influence than he thinks. Otherwise, he is a man of nice value, as a critic.

Then, there is a woman, Mirjana Miočinović, who wrote something about my Mask, which no one else wrote before her. She understood that there is theater there, which is futuristic. There is another woman, Hatidža Krnjević, who also wrote very well.

They approached the work of a critic with great knowledge, with great erudition.

LIFE PASSES, LIKE SPRING, LIKE BIRDS

In almost all your works, you are occupied with the question of the meaning of living, of death, of the human longing for consolation which would achieve reconciliation between Life and Death. You have also several times stated people and works, a philosopher and an artist – whose life and works have always been a consolation for you. What has connected you so deeply to Socrates and Michelangelo?

In almost all your works, you are occupied with the question of the meaning of living, of death, of the human longing for consolation which would achieve reconciliation between Life and Death. You have also several times stated people and works, a philosopher and an artist – whose life and works have always been a consolation for you. What has connected you so deeply to Socrates and Michelangelo?

The question about the meaning of life, and about death, is awaiting every man, sooner or later. The wish for consolation, as well, in life.

However, you, which is understandable, see completely differently in the age of youth, which is madness, and which is a merry, careless life. And when you’re in your eighties, you inevitably think about death.

Life at the end is a life of contemplation. When you see peasants in the simplest village in Vojvodina, in Banat, you see them coming out of the house, sitting on the bench every day in the evening. Don’t think they’re talking nonsense, some banal things. They are thinking about the past, how one of their friends has ended and the other stayed alive, what the old man who lost his son is doing.

The entire drama of life takes place, most intensively, at the end of life, in contemplation.

Then you either find meaning to your life, or you don’t, regardless of whether you have fertilized the soil, or literature.

That is how it is in my novels, and poems, all of them.

And Socrates? Socrates dies so peacefully, because he is convinced that it is the meaning of life, that it has to have its end.

Or what happened with Michelangelo, who was completely alone, all his life, but never gave in, not for a single moment. Four days before his death he was changing a sculpture, still working on it, carving, and writing sonnets, which are shocking, which are exquisite poetry.

Dying is most difficult for the masses, for the world. The entire world is scared, because it’s hard to watch death in the eyes. It is consoling, however, if you have something to remember, something beautiful, from your life, and know that death is waiting for you as well, but you’re not afraid of it.

Because it’s clear, life is passing, but passing like spring is passing, like birds are passing. Entirely nice.

You have been studying the life and work of Michelangelo for a long time. Sculptures, paintings, sonnets. Many times, you mentioned that the book is near its end, that you are finishing it. When can we expect it?

I have been working for eight years and been interested in Michelangelo for fifty years.

Now that I, in the past eight years, saw several exhibitions and movies, especially movies, new, American, about him and his paintings, I will make a book about certain things, which I believe are not correct, that they are tendentious, and accordingly, I will calmly tell my opinion.

The book will be completed, soon, and can soon be printed, only if my eyes can last.

Because I write by hand, alone, and then it goes to the machine. Thus, it is pretty exhausting.

***

Short History of Transmission

Jovan Pejčić’s interview with Miloš Crnjanski was published several times after 1973, most often with some plots, errors and damages which cannot be explained as simply ”accidental”. Kasim Prohić published the entire interview in the ”Izraz” magazine, with Pejčić’s introductory note (”Life is passing as spring is passing, as birds are passing. Entirely nice”, ”Izraz”, Sarajevo 1978). A book of interviews with Crnjanski was published in BIGZ in 1992 entitled I Fulfilled My Fate (edited by Zoran Avramović). It includes Pejčić’s interview with Crnjanski, but the mutilated version from ”Student”. Seven years later, the eleventh volume of ”Works of Miloš Crnjanski” (”Essays and Articles II”, edited by Živorad Stojković with associates, Belgrade 1999) also includes the text copied from ”Student”, with the addition of the original introductory note. Finally, ”Naše stvaranje” magazine published the correct version twenty-one years ago (”A true poet can never die before they fulfill their Self, their fate”, ”Naše stvaranje”, Leskovac 2002).

***

Going All the Way or Giving Up

The plot with publishing the interview reminds me of another conversation which Crnjanski had in 1975 with the students of the Faculty of Philology in Belgrade. Answering a question of a poet-beginner, he said that one has the duty to go all the way when they begin something. Or give up on everything and consider, and live in such a way, as if they had never begun anything.